Art Collective That Made Supercut of New York Being Destroyed

The Europahaus, 1 of hundreds of cabarets in Weimar Berlin, 1931

Weimar civilization was the emergence of the arts and sciences that happened in Germany during the Weimar Republic, the latter during that role of the interwar period betwixt Germany'southward defeat in World War I in 1918 and Hitler'due south rise to power in 1933.[1] 1920s Berlin was at the hectic center of the Weimar culture.[one] Although not function of the Weimar Republic, some authors likewise include the German-speaking Austria, and specially Vienna, every bit part of Weimar civilisation.[ii]

Germany, and Berlin in particular, was fertile footing for intellectuals, artists, and innovators from many fields during the Weimar Republic years. The social environment was chaotic, and politics were passionate. German university faculties became universally open to Jewish scholars in 1918. Leading Jewish intellectuals on academy faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim, Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse; philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Edmund Husserl; political theorists Arthur Rosenberg and Gustav Meyer; and many others. 9 German language citizens were awarded Nobel Prizes during the Weimar Republic, 5 of whom were Jewish scientists, including two in medicine.[3] Jewish intellectuals and artistic professionals were among the prominent figures in many areas of Weimar culture.

With the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party and the ascent to power of Adolf Hitler in 1933, many German intellectuals and cultural figures, both Jewish and non-Jewish, fled Deutschland for the Usa, the United Kingdom, and other parts of the world. The intellectuals associated with the Institute for Social Enquiry (besides known every bit the Frankfurt School) fled to the United States and reestablished the Found at the New School for Social Research in New York Urban center. In the words of Marcus Bullock, Emeritus Professor of English at University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, "Remarkable for the mode it emerged from a ending, more than remarkable for the fashion information technology vanished into a notwithstanding greater catastrophe, the world of Weimar represents modernism in its well-nigh brilliant manifestation." The culture of the Weimar menstruation was later reprised past 1960s left-fly intellectuals,[4] especially in France. Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Michel Foucault reprised Wilhelm Reich; Jacques Derrida reprised Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger; Guy Debord and the Situationist International reprised the subversive-revolutionary culture.

[edit]

By 1919, an influx of labor had migrated to Berlin turning it into a fertile footing for the mod arts and sciences, leading to blast in trade, communications and structure. A trend that had begun earlier the Great War was given powerful impetus by fall of the Kaiser and majestic power. In response to the shortage of pre-war accommodation and housing, tenements were built not far from the Kaiser's Stadtschloss and other majestic structures erected in honor of former nobles. Average people began using their backyards and basements to run small shops, restaurants, and workshops. Commerce expanded rapidly, and included the institution of Berlin's first department stores, prior WWI. An "urban trivial bourgeoisie" along with a growing centre class grew and flourished in wholesale commerce, retail trade, factories and crafts.[5]

Types of employment were becoming more modern, shifting gradually but noticeably towards industry and services. Earlier World War I, in 1907, 54.nine% of German workers were manual labourers. This dropped to fifty.one% by 1925. Office workers, managers, and bureaucrats increased their share of the labour marketplace from ten.3% to 17% over the same period. Germany was slowly becoming more urban and eye class. Even so, by 1925, only a tertiary of Germans lived in large cities; the other ii-thirds of the population lived in the smaller towns or in rural areas.[6] The total population of Deutschland rose from 62.4 million in 1920 to 65.ii million in 1933.[seven]

The Wilhelminian values were farther discredited as a consequence of World State of war I and the subsequent inflation, since the new youth generation saw no signal in saving for marriage in such conditions, and preferred instead to spend and enjoy.[8] According to cultural historian Bruce Thompson, the Fritz Lang moving-picture show Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) captures Berlin's postwar mood:[viii]

The moving picture moves from the globe of the slums to the world of the stock exchange then to the cabarets and nightclubs–and everywhere chaos reigns, authority is discredited, power is mad and uncontrollable, wealth inseparable from crime.

Politically and economically, the nation was struggling with the terms and reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles (1919) that concluded World War I and endured punishing levels of inflation.

-

Children being fed by a soup kitchen, 1924.

-

A homo reads a sign advertising "Attending, Unemployed, Haircut 40 pfennigs, Shave fifteen pfennigs", 1927.

-

An elderly woman gathers vegetable waste material tossed from a vegetable seller's wagon for her dejeuner, 1923.

-

Sketch of a woman in a café by Lesser Ury for a Berlin paper, 1925.

Sociology [edit]

During the era of the Weimar Commonwealth, Germany became a center of intellectual thought at its universities, and near notably social and political theory (especially Marxism) was combined with Freudian psychoanalysis to grade the highly influential subject of Critical Theory—with its development at the Institute for Social Enquiry (also known as the Frankfurt School) founded at the University of Frankfurt am Main.

The most prominent philosophers with which the and then-called 'Frankfurt School' is associated were Erich Fromm, Herbert Marcuse, Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Jürgen Habermas and Max Horkheimer.[nine] Among the prominent philosophers not associated with the Frankfurt School were Martin Heidegger and Max Weber.

The German language philosophical anthropology movement too emerged at this time.[10]

Science [edit]

This image high-speed train travelled at 230 km per hour from Hamburg to Berlin, 1931. It was congenital past the Krukenberg engineering company.

An early calculator shown at an office engineering science exhibition, Berlin, 1931. Information technology was promoted as costing 3500 marks.

Many foundational contributions to breakthrough mechanics were fabricated in Weimar Germany or by German scientists during the Weimar flow. While temporarily at the University of Copenhagen, German physicist Werner Heisenberg formulated his Uncertainty principle, and, with Max Born and Pascual Jordan, accomplished the kickoff complete and right definition of quantum mechanics, through the invention of Matrix mechanics.[11]

Göttingen was the center of research in aero- and fluid-dynamics in the early 20th century. Mathematical aerodynamics was founded by Ludwig Prandtl before World War I, and the piece of work continued at Göttingen until interfered with in the 1930s and prohibited in the late 1940s. It was in that location that compressibility drag and its reduction in aircraft was start understood. A striking example of this is the Messerschmitt Me 262, which was designed in 1939, but resembles a modernistic jet send more than that it did other tactical aircraft of its fourth dimension.

Albert Einstein rose to public prominence during his years in Berlin, being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921. He was forced to flee Germany and the Nazi regime in 1933.

Physician Magnus Hirschfeld established the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexology) in 1919, and it remained open until 1933. Hirschfeld believed that an understanding of homosexuality could exist arrived at through scientific discipline. Hirschfeld was a vocal advocate for homosexual, bisexual, and transgender legal rights for men and women, repeatedly petitioning parliament for legal changes. His Institute likewise included a museum. The Institute, museum and the Institute'southward library and archives were all destroyed by the Nazi regime in 1933.

If we also include the German-speaking Vienna, during the Weimar years Mathematician Kurt Gödel published his groundbreaking Incompleteness Theorem.[12]

Pedagogy [edit]

New schools were frequently established in Weimar Deutschland to engage students in experimental methods of learning. Some were office of an emerging trend that combined inquiry into physical move and overall health, for example Eurythmy ensembles in Stuttgart that spread to other schools. Philosopher Rudolf Steiner established the start Waldorf pedagogy school in 1919, using a educational activity also known as the Steiner method, which spread worldwide. Many Waldorf schools are in beingness today.

The arts [edit]

The 14 years of the Weimar era were besides marked past explosive intellectual productivity. German language artists fabricated multiple cultural contributions in the fields of literature, art, architecture, music, trip the light fantastic toe, drama, and the new medium of the motion motion-picture show. Political theorist Ernst Bloch described Weimar civilisation as a Periclean Age.

German visual art, music, and literature were all strongly influenced by High german Expressionism at the start of the Weimar Republic. By 1920, a sharp plow was taken towards the Neue Sachlichkeit New Objectivity outlook. New Objectivity was non a strict move in the sense of having a clear manifesto or set of rules. Artists gravitating towards this aesthetic divers themselves by rejecting the themes of expressionism—romanticism, fantasy, subjectivity, raw emotion and impulse—and focused instead on precision, deliberateness, and depicting the factual and the real.

Kirkus Reviews remarked upon how much Weimar art was political:[xiii]

fiercely experimental, iconoclastic and left-leaning, spiritually hostile to large business and bourgeois society and at daggers drawn with Prussian militarism and authoritarianism. Not surprisingly, the sometime autocratic German establishment saw it every bit 'corrupt fine art', a view shared by Adolf Hitler who became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933. The public burning of 'unGerman books' by Nazi students on Unter den Linden on tenth May 1933 was but a symbolic confirmation of the catastrophe which befell not only Weimar fine art under Hitler but the whole tradition of enlightenment liberalism in Germany, a tradition whose origins went dorsum to the 18th century city of Weimar, dwelling house to both Goethe and Schiller.

One of the first major events in the arts during the Weimar Republic was the founding of an system, the Novembergruppe (November Group) on Dec 3, 1918. This group was established in the aftermath of the November beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–1919, when Communists, anarchists and pro-republic supporters had fought in the streets for command of the government. In 1919, the Weimar Commonwealth was established. Around 100 artists of many genres who identified themselves equally avant-garde joined the November Group. They held xix exhibitions in Berlin until the group was banned past the Nazi regime in 1933. The group as well had chapters throughout Deutschland during its existence, and brought the German avant-garde art scene to world attention past holding exhibits in Rome, Moscow and Japan.

Its members also belonged to other art movements and groups during the Weimar Democracy era, such as builder Walter Gropius (founder of Bauhaus), and Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht (agitprop theatre).[xiv] The artists of the November Group kept the spirit of radicalism alive in German language fine art and culture during the Weimar Democracy. Many of the painters, sculptors, music composers, architects, playwrights, and filmmakers who belonged to information technology, and nevertheless others associated with its members, were the aforementioned ones whose art would afterward be denounced as "degenerate art" past Adolf Hitler.

Visual arts [edit]

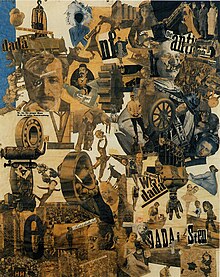

Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919) past Hannah Höch, a Dada pioneer of photomontage art.

The Weimar Republic era began in the midst of several major movements in the fine arts that continued into the 1920s. German Expressionism had begun before World State of war I and continued to have a strong influence throughout the 1920s, although artists were increasingly likely to position themselves in opposition to expressionist tendencies every bit the decade went on.

Dada had begun in Zurich during World War I, and became an international phenomenon. Dada artists met and reformed groups of like-minded artists in Paris, Berlin, Cologne, and New York City. In Frg, Richard Huelsenbeck established the Berlin group, whose members included Jean Arp, John Heartfield, Wieland Hertzfelde, Johannes Baader, Raoul Hausmann, George Grosz and Hannah Höch. Machines, applied science, and a potent Cubism element were features of their work. Jean Arp and Max Ernst formed a Cologne Dada grouping, and held a Dada Exhibition there that included a work by Ernst that had an axe "placed at that place for the convenience of anyone who wanted to attack the piece of work".[xv] Kurt Schwitters established his own solitary one-man Dada "group" in Hanover, where he filled two stories of a house (the Merzbau) with sculptures cobbled together with found objects and ephemera, each room dedicated to a notable creative person friend of Schwitter's. The house was destroyed by Centrolineal bombs in 1943.[15]

The New Objectivity artists did not belong to a formal group. Diverse Weimar Republic artists were oriented towards the concepts associated with it, however. Broadly speaking, artists linked with New Objectivity include Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Conrad Felixmüller, Christian Schad, and Rudolf Schlichter, who all "worked in different styles, only shared many themes: the horrors of war, social hypocrisy and moral decadence, the plight of the poor and the rise of Nazism".[sixteen]

Otto Dix and George Grosz referred to their own move as Verism, a reference to the Roman classical Verism approach called verus, meaning "truth", warts and all. While their art is recognizable equally a biting, cynical criticism of life in Weimar Federal republic of germany, they were striving to portray a sense of realism that they saw missing from expressionist works.[17] New Objectivity became a major undercurrent in all of the arts during the Weimar Republic.

Blueprint [edit]

The pattern field during the Weimar Republic witnessed some radical departures from styles that had come before it. Bauhaus-style designs are distinctive, and synonymous with mod blueprint. Designers from these movements turned their energy towards a diversity of objects, from furniture, to typography, to buildings. Dada's goal of critically rethinking design was similar to Bauhaus, simply whereas the earlier Dada motion was an aesthetic approach, the Bauhaus was literally a school, an institution that combined a sometime school of industrial design with a school of arts and crafts. The founders intended to fuse the arts and crafts with the applied demands of industrial blueprint, to create works reflecting the New Objectivity aesthetic in Weimar Frg. Walter Gropius, a founder of the Bauhaus school, stated "we want an architecture adapted to our world of machines, radios and fast cars."[18] Berlin and other parts of Deutschland all the same accept many surviving landmarks of the architectural way at the Bauhaus. The mass housing projects of Ernst May and Bruno Taut are testify of markedly creative designs being incorporated every bit a major feature of new planned communities. Erich Mendelsohn and Hans Poelzig are other prominent Bauhaus architects, while Mies van der Rohe is noted for his architecture and his industrial and household furnishing designs.

Painter Paul Klee was a faculty member of Bauhaus. His lectures on modern art (now known as the Paul Klee Notebooks) at the Bauhaus have been compared for importance to Leonardo's Treatise on Painting and Newton'due south Principia Mathematica, constituting the Principia Aesthetica of a new era of art;[19] [twenty]

Bruno Taut and Adolf Behne founded the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Workers' Council for Art) in 1919. Their aim was to assert force per unit area for political change on the Weimar Democracy government, that would benefit the management of architecture and arts management, similar to Germany's big councils for workers and soldiers. This Berlin system had around fifty members.[21]

Withal another influential amalgamation of architects was the group Der Ring (The Ring) established by x architects in Berlin in 1923-24, including: Otto Bartning, Peter Behrens, Hugo Häring, Erich Mendelsohn, Mies van der Rohe, Bruno Taut and Max Taut. The group promoted the progress of modernism in architecture.

-

Armchair, model MR-xx, 1927, by designer Mies van der Rohe, manufactured by Bamberg Metallwerkstatten, Berlin.

-

-

A highrise of the German Borsig company, made in the spirit of brick expressionism past Eugen Schmohl (1922–1924). It still stands in the Tegel district of Berlin.

Literature [edit]

Writers such as Alfred Döblin, Erich Maria Remarque and the brothers Heinrich and Thomas Mann presented a bleak look at the world and the failure of politics and society through literature. Foreign writers besides travelled to Berlin, lured past the metropolis'southward dynamic, freer culture. The decadent cabaret scene of Berlin was documented by Britain'southward Christopher Isherwood, such equally in his novel Goodbye to Berlin which was later transposed to the play I Am a Camera, which was adjusted into the musical and musical moving-picture show Cabaret.[8]

Eastern religions such as Buddhism were becoming more attainable in Berlin during the era, every bit Indian and East Asian musicians, dancers, and even visiting monks came to Europe. Hermann Hesse embraced Eastern philosophies and spiritual themes in his novels.

Cultural critic Karl Kraus, with his brilliantly controversial magazine Die Fackel, advanced the field of satirical journalism, condign the literary and political conscience of this era.[22]

Weimar Germany likewise saw the publication of some of the globe's first openly gay literature, from authors such as Klaus Mann, Anna Elisabet Weirauch, Christa Winsloe, Erich Ebermayer, and Max René Hesse.[23] [24] [25]

Theatre [edit]

The theatres of Berlin and Frankfurt am Main were graced with drama by Ernst Toller, Bertolt Brecht, cabaret, and stage management by Max Reinhardt and Erwin Piscator. Many theatre works were sympathetic towards Marxist themes, or were overt experiments in propaganda, such as the agitprop theatre by Brecht and Weill. Agitprop theatre is named through a combination of the words "agitation" and "propaganda". Its aim was to add elements of public protest (agitation) and persuasive politics (propaganda) to the theatre, in the hope of creating a more than activist audience. Amongst other works, Brecht and Kurt Weill collaborated on the musical or opera The Threepenny Opera (1928), likewise filmed, which remains a popular evocation of the period.

Toller was the leading German expressionist playwright of the era. He afterward became one of the leading proponents of New Objectivity in the theatre. The avant-garde theater of Bertolt Brecht and Max Reinhardt in Berlin was the nearly avant-garde in Europe, existence rivaled merely by that of Paris.[thirteen]

The Weimar years saw a flourishing of political and grotesque cabaret which, at least for the English language-speaking world, has become iconic for the period through works such as The Berlin Stories by the English writer Christopher Isherwood, who lived in Berlin from 1929-33.[26] The musical and and so the film Cabaret were based upon Isherwood'due south misadventures at Nollendorfstrasse 17 in the Schöneberg district where he lived with cabaret vocalizer Jean Ross.[26] The principal center for political cabaret was Berlin, with performers like comedian Otto Reutter.[27] Karl Valentin was a master of grotesque cabaret.

Music [edit]

Concert halls heard the atonal and modern music of Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg, and Kurt Weill. Hanns Eisler and Paul Dessau were other modernist composers of the era. Richard Strauss, in his 50s at the start of the period, continued to compose, generally operas including Intermezzo (1924) and Die ägyptische Helena (1928).

Modern trip the light fantastic toe [edit]

Rudolf von Laban and Mary Wigman laid the foundations for the development of contemporary dance.

Cinema [edit]

At the commencement of the Weimar era, cinema meant silent films. Expressionist films featured plots exploring the nighttime side of human nature. They had elaborate expressionist design sets, and the style was typically nightmarish in temper. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), directed by Robert Wiene, is usually credited as the start German expressionist film. The sets depict distorted, warped-looking buildings in a German boondocks, while the plot centres around a mysterious, magical cabinet that has a articulate association with a casket. F. W. Murnau's vampire horror film Nosferatu was released in 1922. Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) was described as "a sinister tale" that portrays "the corruption and social chaos so much in evidence in Berlin and more generally, according to Lang, in Weimar Germany".[28] Futurism is another favourite expressionist theme, shown corrupted into a force of oppression in the dystopia of Urban center (1927). The cocky-deluded lead characters in many expressionist films echo Goethe'south Faust, and Murnau indeed retold the tale in his moving-picture show Faust.

German expressionism was not the ascendant blazon of popular moving picture in Weimar Germany and were outnumbered by the production of costume dramas, often about folk legends, which were enormously popular with the public.[28] The Weimar era's most groundbreaking film studio was the UFA studio.

Silent films continued to exist made throughout the 1920s, in parallel with the early years of sound films during the final years of the Weimar Republic. Silent films had sure advantages for filmmakers, such equally the ability to hire an international cast, since spoken accents were irrelevant. Thus, American and British actors were easily able to interact with German language directors and cast-members on films fabricated in Germany (for example, the collaborations of Georg Pabst and Louise Brooks). When sound films started existence produced in Deutschland, some filmmakers experimented with versions in more than one linguistic communication, filmed simultaneously.

When the musical The Threepenny Opera was filmed by managing director Georg Pabst, he filmed the first version with a French-speaking bandage (1930), and then a 2nd version with a German-speaking cast (1931). An English version was planned merely never materialized.[29] The Nazis destroyed the original negative print of the High german version in 1933, and it was reconstructed after the War concluded.[30] The Blue Angel (1930), directed past Josef von Sternberg with the leads played by Marlene Dietrich and Emil Jannings, was filmed simultaneously in English and High german (a dissimilar supporting bandage was used for each version). Although it was based on a 1905 story written by Heinrich Mann, the pic is frequently seen as topical in that information technology depicts the doomed romance between a Berlin professor and a cabaret dancer. However, critics differ on this interpretation, with the absence of mod urban amenities such as automobiles being noted.[31]

Cinema in Weimar culture did not shy abroad from controversial topics, but dealt with them explicitly. Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst and starring Louise Brooks, deals with a immature adult female who is thrown out of her dwelling house later having an illegitimate kid, and is then forced to get a prostitute to survive. This trend of dealing frankly with provocative textile in movie house began immediately after the stop of the War. In 1919, Richard Oswald directed and released two films, that met with press controversy and action from police force vice investigators and regime censors. Prostitution dealt with women forced into "white slavery", while Different from the Others dealt with a homosexual human being's conflict betwixt his sexuality and social expectations.[32] By the end of the decade, like material met with little, if any opposition when it was released in Berlin theatres. William Dieterle's Sex in Bondage (1928), and Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929) bargain with homosexuality among men and women, respectively, and were not censored. Homosexuality was as well present more than tangentially in other films from the period.

Philosophy [edit]

Philosophy during the Weimar Democracy pursued paths of enquiry into scientific fields such as mathematics and physics. Leading scientists became associated every bit a group that was called the Berlin Circle. Among many influential thinkers, Carl Hempel was a strong influence in the group. Built-in in Berlin, Hempel attended the University of Göttingen and the University of Heidelberg, so returned to Berlin, where he was taught past influential physicists Hans Reichenbach and Max Planck, and logistics with mathematician John von Neumann. Reichenbach introduced Hempel to the Vienna Circle, who were an existing informal clan of "scientifically interested philosophers and philosophically interested scientists", as Hempel put it.[33] Hempel was intrigued by the logical positivism ideas discussed by the Vienna Circle, and he developed a similar network, the Berlin Circle. Hempel's reputation has grown to the extent that he is now considered one of the leading scientific philosophers of the 20th century.[33] Richard von Mises was active in both groups.

Germany's virtually influential philosopher during the Weimar Republic years, and perhaps of the 20th century, was Martin Heidegger. Heidegger published one of the cornerstones of 20th-century philosophy during this menses, Being and Time (1927). Being and Time influenced successive generations of philosophers in Europe and the U.s.a., particularly in the areas of phenomenology, existentialism, hermeneutics and deconstruction. Heidegger'due south work congenital on, and responded to, the earlier explorations of phenomenology by another Weimar era philosopher, Edmund Husserl.

The intersection of politics and philosophy inspired other philosophers in Weimar Germany, when radical politics included many thinkers and activists across the political spectrum. During his 20s, Herbert Marcuse was a student in Freiburg, where he went to report nether Martin Heidegger, one of Frg's most prominent philosophers. Marcuse himself later became a driving strength in the New Left in the United states. Ernst Bloch, Max Horkheimer and Walter Benjamin all wrote near Marxism and politics in addition to other philosophical topics. From the perspective of Jewish philosophers in Deutschland, they also considered the problems posed by the "Jewish question".[34] [35] Political philosophers Leo Strauss and Hannah Arendt received their university instruction during the Weimar Republic and moved in Jewish intellectual circles in Berlin, and were associated with Norbert Elias, Leo Löwenthal, Karl Löwith, Julius Guttmann, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Franz Rosenzweig, Gershom Scholem, and Alexander Altmann. Strauss and Arendt, along with Marcuse and Benjamin, were among the Jewish intellectuals who managed to flee the Nazi regime, eventually emigrating to the United states of america. Carl Schmitt, a legal and political scholar, was as well a vocal fascist supporter of both the Nazi regime and Spain's Franco; yet, he published works of political philosophy that remained studied by philosophers and political scholars with radically different views, such as Alain Badiou, Slavoj Žižek, and his contemporaries Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, and Leo Strauss.

Health and self-improvement [edit]

Students at a boarding school in Hanover, offset each 24-hour interval with 8 o'clock rhythmic dancing and jumping exercises, 1931.

Germany had many innovators in wellness treatment, some more questionable than others, in the decades leading up to World War I. As a grouping, they were collectively known as part of the Lebensreform, or Life Reform, motion. During the Weimar years, some of these found traction with the German language public, particularly in Berlin.

Some innovations had lasting influence. Joseph Pilates adult much of his Pilates organization of physical grooming during the 1920s. Expressionist dance teachers such every bit Rudolf Laban had an of import impact on Pilates' theories.

Nacktkultur, called naturism or modern nudism in English, was pioneered by Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach in Vienna in the late 1890s. Resorts for naturists were established at a rapid pace along the northern coast of Germany during the 1920s, and by 1931, Berlin itself had 40 naturists' societies and clubs. A variety of periodicals on the topic were too regularly published.[36]

Philosopher Rudolf Steiner, like Diefenbach, was a follower of Theosophy. Steiner had an enormous influence on the alternative health motility earlier his decease in 1925 and far across. With Ita Wegman, he developed anthroposophical medicine. The integration of spirituality and homeopathy is controversial and has been criticized for having no footing in science.[37]

Steiner was too an early on proponent of organic agriculture, in the class of a holistic concept later called biodynamic agriculture. In 1924 he delivered a serial of public lectures on the topic, which were and so published.[38]

Aufklärungsfilme (enlightenment films) supported the idea of teaching the public about important social issues, such equally alcohol and drug addiction, venereal affliction, homosexuality, prostitution, and prison reform.[39]

LGBT status [edit]

Weimar Germany experienced an increment in the vocalization and congregation of the LGBT community, partially due to the leniency of federal censorship. The menstruation marked an influx in lesbian and gay media as publishers took advantage of ambiguously worded censorship laws in the Weimar Constitution. And then in 1921, the German Reichsgericht ruled that homosexual themes in printing were not necessarily obscene unless erotic in nature. [40]

Gay magazines disseminated meeting spots for members of the LGBT to get together and enabled the formation of clubs referred to as "friendship leagues." Some of these leagues would eventually integrate with the German League for Human Rights.[40]

Weimar-era Germany besides witnessed the emergence of the world'south first lesbian mag, Die Freundin. Although there were at least five lesbian magazines available at the time to more than one million readers across German-speaking countries, Die Freundin was the almost popular.[41] Published from 1924 to 1933, the magazine featured short stories as well as information most lesbian meetings and nightspots before information technology was ultimately close down after the Nazis rose to power.[41]

In 1928, the commencement guide to the lesbian club scene was published by Ruth Roellig entitled "Ruth Roellig's Berlins lesbische Frauen (Berlin'south Lesbian Women)." This guide immune women in Berlin to connect and larn more nearly the lesbian community.[42]

Despite the illegality of homosexuality during this time period, references to homosexual relationships in cinema grew essentially. 2 well-known films from Weimar Germany that centered around homosexual relationships are Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others), which centered around a relationship between ii men, and Madchen in Uniform (Girls in Uniform), which focused on a lesbian relationship betwixt a teacher and pupil. Both of these films received wonderful critical reviews and were commercial hits, opening in Berlin's tiptop theatres. Despite the wonderful reviews, there was still public outcry over Anders als dice Andern including riots at the cinemas where information technology opened and it was fifty-fifty banned in various theatres including in Munich, Vienna, and Stuttgart.[43]

Berlin's reputation for decadence [edit]

A liquor-seller after closing time on the route. His activity was illegal and the liquor, which cost one mark per glass, was often of quite dubious origin. The seller constantly changed his location

Prostitution rose in Berlin and elsewhere in the areas of Europe left ravaged by World War I. This means of survival for drastic women, and sometimes men, became normalized to a degree in the 1920s. During the war, venereal diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea spread at a rate that warranted government attending.[44] Soldiers at the forepart contracted these diseases from prostitutes, so the German army responded by granting approval to sure brothels that were inspected by their ain medical doctors, and soldiers were rationed coupon books for sexual services at these establishments.[45] Homosexual behaviour was as well documented among soldiers at the front. Soldiers returning to Berlin at the stop of the War had a different mental attitude towards their own sexual behaviour than they had a few years previously.[45] Prostitution was frowned on by respectable Berliners, just it connected to the betoken of becoming entrenched in the city's underground economy and culture. First women with no other ways of support turned to the merchandise, and so youths of both genders.

Crime in general developed in parallel with prostitution in the urban center, start as petty thefts and other crimes linked to the need to survive in the war's aftermath. Berlin eventually acquired a reputation as a hub of drug dealing (cocaine, heroin, tranquilizers) and the black market. The police identified 62 organized criminal gangs in Berlin, called Ringvereine.[46] The German public also became fascinated with reports of homicides, especially "animalism murders" or Lustmord. Publishers met this need with cheap criminal novels called Krimi, which like the flick noir of the era (such equally the classic Grand), explored methods of scientific detection and psychosexual assay.[47]

Apart from the new tolerance for behaviour that was technically nevertheless illegal, and viewed by a large part of society as immoral, in that location were other developments in Berlin culture that shocked many visitors to the city. Thrill-seekers came to the city in search of take a chance, and booksellers sold many editions of guide books to Berlin'due south erotic night entertainment venues. There were an estimated 500 such establishments, that included a large number of homosexual venues for men and for women; sometimes transvestites of one or both genders were admitted, otherwise there were at least five known establishments that were exclusively for a transvestite clientele.[48] There were also several nudist venues. Berlin also had a museum of sexuality during the Weimar menstruum, at Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld'due south Establish of Sexology.[49] These were nearly all closed when the Nazi regime became a dictatorship in 1933.

Artists in Berlin became fused with the metropolis'south underground culture as the borders betwixt cabaret and legitimate theatre blurred. Anita Berber, a dancer and extra, became notorious throughout the city and beyond for her erotic performances (equally well as her cocaine habit and erratic behaviour). She was painted by Otto Dix, and socialized in the same circles as Klaus Mann.

Gallery of 1920s Berlin cultural life [edit]

1920s Berlin was a city of many social contrasts. While a large part of the population connected to struggle with loftier unemployment and deprivations in the aftermath of World War I, the upper class of society, and a growing middle class, gradually rediscovered prosperity and turned Berlin into a cosmopolitan metropolis.

-

Prostitutes purchase cocaine capsules from a drug dealer in Berlin, 1930. The capsules sold for five marks each.

-

International Women's Union Congress in Berlin, 1929.

See also [edit]

- Aftermath of Globe War I

- Movie house of Germany

- Critical Theory

- Civilization of Frg

- Dada

- Degenerate fine art

- Expressionism

- Futurism

- Frg

- High german Expressionism

- Gleichschaltung

- Glitter and Doom - Showroom of Art in the Weimar Commonwealth

- Glossary of the Weimar Commonwealth

- Golden Twenties

- History of Deutschland

- Kultur

- Literature of World War I

- Lost Generation

- Modernism

- Nazi Frg

- New Objectivity

- Postal service-Earth War I recession

- Postal service-expressionism

- Reactionary modernism

- Roaring Twenties

- Surrealism

- Weimar Timeline

- Weimaraner

References [edit]

- ^ a b Finney (2008)

- ^ Congdon, Lee (1991) volume Synopsis for Exile and Social Idea : Hungarian Intellectuals in Frg and Austria, 1919–1933, Princeton University Press

- ^ Niewyk, Donald L. (2001). The Jews in Weimar Germany. Transaction Publishers. pp. 39–40. ISBN978-0-7658-0692-5.

- ^ Kirkus Reviews, December 01, 1974. Review of Laqueur, Walter Weimar: A cultural history, 1918–1933

- ^ Schrader, Barbel. "The 'Aureate' Twenties: Fine art and Literature in the Weimar Republic". Yale Academy Press, 1988, p.25-27.

- ^ Peukert, Detlev (1993). The Weimar Republic: the crisis of classical modernity. Macmillan. pp. 10. ISBN978-0-8090-1556-half dozen.

- ^ Peukert, Detlev (1993). The Weimar Democracy: the crunch of classical modernity. Macmillan. pp. seven. ISBN978-0-8090-1556-6.

- ^ a b c Bruce Thompson, Academy of California, Santa Cruz, lecture on WEIMAR CULTURE/KAFKA'S PRAGUE

- ^ Outhwaite, William. 1988. Habermas: Key Contemporary Thinkers 2nd Edition (2009). p5. ISBN 978-0-7456-4328-1

- ^ Halton, Eugene (1995) Insufficient of reason: on the refuse of social thought and prospects for its renewal p.52

- ^ History of Quantum Structures and IQSA - The Birth of Quantum Mechanics

- ^ Selz, pp.27

- ^ a b Kirkus United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland review of Laqueur, Walter Weimar: A cultural history, 1918–1933

- ^ Dempsey, Amy (2010). Styles, Schools and Movements: The Essential Encyclopaedic Guide to Mod Art. Thames & Hudson. pp. 128–9. ISBN978-0-500-28844-3.

- ^ a b Dempsey, Amy (2010). Styles, Schools and Movements: The Essential Encyclopaedic Guide to Modern Art. Thames & Hudson. p. 118. ISBN978-0-500-28844-three.

- ^ Dempsey, Amy (2010). Styles, Schools and Movements: The Essential Encyclopaedic Guide to Modern Fine art. Thames & Hudson. p. 149. ISBN978-0-500-28844-3.

- ^ Barton, Brigid S. (1981). Otto Dix and Dice neue Sachlichkeit, 1918-1925. UMI Inquiry Printing. p. 83. ISBN978-0-8357-1151-vii.

- ^ Curtis, William (1987). "Walter Gropius, German language Expressionism, and the Bauhaus". Modernistic Architecture Since 1900 (2nd Ed. ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 309–316. ISBN978-0-xiii-586694-eight.

- ^ Guilo Carlo Argan "Preface", Paul Klee, The Thinking Eye, (ed. Jürg Spiller), Lund Humphries, London, 1961, p.thirteen.

- ^ Herbert Read (1959) A coincise history of modern painting, London, p.186

- ^ Dempsey, Amy (2010). Styles, Schools and Movements: The Essential Encyclopaedic Guide to Modern Art. Thames & Hudson. p. 126. ISBN978-0-500-28844-3.

- ^ Selz 45

- ^ Chamberlin, Rick (2005). "Coming out of His Begetter'south Closet: Klaus Mann'southward "Der fromme Tanz" as an Anti-"Tod in Venedig"". Monatshefte. 97 (4): 615–627. doi:10.3368/grand.XCVII.iv.615. JSTOR 30154241.

- ^ Huneke, Samuel Clowes (2013). "The Reception of Homosexuality in Klaus Isle of mann'south Weimar Era Works". Monatshefte. 105 (i): 86–100. doi:ten.1353/mon.2013.0027.

- ^ Nenno, Nancy P. (1998). "Bildung and Want: Anna Elisabet Weirauch's Der Skorpion". Queering the Canon: Defying Sights in High german Literature and Culture: 207–221.

- ^ a b Doyle, Rachel (12 April 2013). "Looking for Christopher Isherwood'due south Berlin". The New York Times. p. TR10. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ Peter Gay (1968) Weimar Civilization: The Outsider as Insider p.131

- ^ a b Hayward, Susan (2006). Cinema studies: the key concepts. Taylor & Francis. p. 171. ISBN978-0-415-36781-3.

- ^ Robertson, James Crighton (1993). The hidden movie house: British film censorship in activeness, 1913–1975. Psychology Press. p. 53. ISBN978-0-415-09034-half-dozen.

- ^ Robertson, James Crighton (1993). The hidden movie theater: British picture censorship in activity, 1913–1975. Psychology Press. p. 54. ISBN978-0-415-09034-half-dozen.

- ^ Gemünden, Gerd & Mary R. Desjardins (2006). Dietrich Icon. Duke University Press. pp. 147–viii. ISBN978-0-8223-3819-2.

- ^ Gordon, Mel (2006). The Seven Addictions and Five Professions of Anita Berber. Los Angeles: Feral Business firm. pp. 55–half dozen. ISBN978-one-932595-12-3.

- ^ a b Martin, Robert M. & Andrew Bailey (2011). First Philosophy: Key Problems and Readings in Philosophy, Volume 2. Broadview Press. p. 206. ISBN978-i-55111-973-1.

- ^ Geller, Jay (January 2012). Walter Benjamin Reproducing the Smell of the Messianic (Walter Benjamin Reproducing the Smell of the Messianic Jay Geller DOI:10.5422/fordham/9780823233618.003.0010 ed.). Fordham Scholarship Online. doi:10.5422/fordham/9780823233618.001.0001. ISBN978-0-8232-3361-8.

- ^ Marcuse, Herbert (2011). Kellner, Douglas; Clayton Pierce; Tyson Lewis (eds.). Philosophy, Psychoanalysis, and Emancipation. Taylor & Francis. p. 3 footnote four. ISBN978-0-415-13784-iii.

- ^ Gordon, Mel (2006). Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin . Los Angeles: Feral Firm. pp. 132. ISBN978-1-932595-xi-half dozen.

- ^ Ernst, Edzard (2004). "Anthroposophical medicine: A systematic review of randomised clinical trials". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 116 (4): 128–thirty. doi:ten.1007/BF03040749. PMID 15038403.

- ^ Paull, John (2011). "The Secrets of Koberwitz: The Improvidence of Rudolf Steiner's Agriculture Course and the Founding of Biodynamic Agronomics". Journal of Social Inquiry and Policy. ii (1): 19–twenty.

- ^ Biro, Matthew (2009). The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin . University of Minnesota Press. pp. 308. ISBN978-0-8166-3619-8.

- ^ a b Marhoefer, Laurie (2015). ""THE Book WAS A REVELATION, I RECOGNIZED MYSELF IN IT": Lesbian sexuality, censorship, and the queer press in weimar-era germany". Journal of Women'due south History. 27: 62–86 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Espinaco-Virseda, Angeles (2004-04-01). ""I feel that I vest to y'all": Subculture, Die Freundin and Lesbian Identities in Weimar Germany". spacesofidentity.net. doi:10.25071/1496-6778.8015. ISSN 1496-6778.

- ^ Espinaco-Virseda, Angeles (2004-04-01). ""I experience that I belong to you": Subculture, Dice Freundin and Lesbian Identities in Weimar Germany". spacesofidentity.net. doi:x.25071/1496-6778.8015. ISSN 1496-6778.

- ^ Dyer, Richard (1990). "Less and More than Women and Men: Lesbian and Gay Cinema in Weimar Germany". New High german Critique (51): five. doi:10.2307/488171. ISSN 0094-033X.

- ^ Gordon, Mel (2006). Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin . Los Angeles: Feral Business firm. pp. 16. ISBN978-i-932595-11-6.

- ^ a b Gordon, Mel (2006). Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin . Los Angeles: Feral Firm. pp. 17. ISBN978-1-932595-11-6.

- ^ Gordon, Mel (2006). Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin . Los Angeles: Feral House. pp. 242. ISBN978-1-932595-xi-6.

- ^ Gordon, Mel (2006). Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic Globe of Weimar Berlin . Los Angeles: Feral Business firm. pp. 229. ISBN978-one-932595-eleven-6.

- ^ Gordon, Mel (2006). Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin . Los Angeles: Feral Business firm. pp. 256. ISBN978-1-932595-11-6.

- ^ Gordon, Mel (2006). Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin . Los Angeles: Feral House. pp. 256–7. ISBN978-1-932595-11-six.

Bibliography [edit]

- Becker, Sabina. Neue Sachlichkeit. Köln: Böhlau, 2000. Impress.

- Gail Finney (2008) WEIMAR CULTURE: Defeat, the Roaring Twenties, the Rise of Nazism, Courses overview of program The Roaring Twenties in Frg

- Gay, Peter. Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1981.

- Gordon, Peter Eastward., and John P. McCormick, eds. Weimar Thought: A Contested Legacy (Princeton U.P. 2013) 451 pages; scholarly essays on constabulary, civilisation, politics, philosophy, scientific discipline, art and architecture

- Hermand, Jost and Frank Trommler. Die Kultur der Weimarer Republik. Frankfurt am Master: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1989.

- Jelavich, Peter (2009). Berlin Alexanderplatz: Radio, Film, and the Decease of Weimar Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-25997-three.

- Kaes, Anton, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg. The Weimar Democracy Sourcebook. Berkeley: Academy of California Press, 1995.

- Lethen, Helmut. Cool Carry: The Culture of Distance in Weimar Deutschland. Berkeley: Academy of California Press, 2002.

- Lindner, Martin. Leben in der Krise. Zeitromane der neuen Sachlichkeit und die intellektuelle Mentalität der klassischen Moderne. Stuttgart: Metzler, 1994.

- Martin Mauthner: High german Writers in French Exile, 1933–1940, London: 2007; ISBN 9780853035404.

- Peukert, Detlev. The Weimar Republic: the Crunch of Classical Modernity. New York: Hill and Wang, 1992.

- Schrader, Barbel. "The 'Golden' Twenties: Art and Literature in the Weimar Republic". Yale Academy Press, 1988, p. 25-27.

- Schütz, Erhard H. Romane Der Weimarer Republik. München: W. Fink, 1986. Print.

- Peter Selz (2004) Across the Mainstream: L years of Curating Modern and Contemporary Art. lectures delivered at Duke University, September 10, 2004.

- Weitz, Eric D. Weimar Germany: Hope and Tragedy. Princeton, N.J: Princeton Academy Press, 2007. Print.

- Willett, John. Fine art and Politics in the Weimar Flow: The New Sobriety, 1917–1933. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978. Impress.

External links [edit]

- A site virtually art, literature and politics in the Weimar era

elsberryprepertion63.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weimar_culture

0 Response to "Art Collective That Made Supercut of New York Being Destroyed"

Postar um comentário